The seven wastes

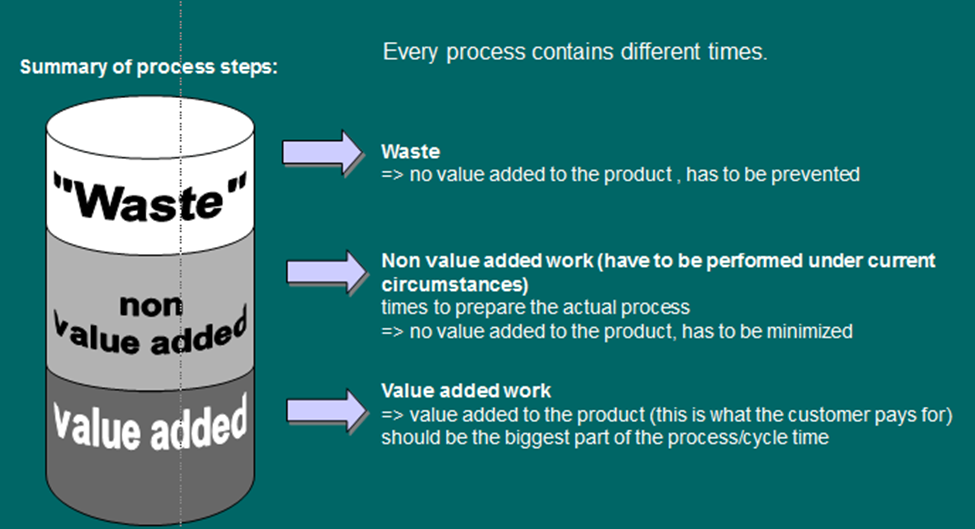

One of the key steps in Lean and TPS is the identification of which steps add value and which do not. By classifying all the process activities into these two categories it is then possible to start actions for improving the former and eliminating the latter. Some of these definitions may seem rather ‘idealist’ but this tough definition is seen as important to the effectiveness of this key step. Once value-adding work (actual work) has been separated from waste then waste can be subdivided into ‘needs to be done (auxiliary work) but non-value adding’ waste and pure waste. The clear identification of ‘non-value adding work’, as distinct from waste or work, is critical to identifying the assumptions and beliefs behind the current work process and to challenging them in due course.

The expression “Learning to see” comes from an ever developing ability to see waste where it was not perceived before. Many have sought to develop this ability by ‘trips to Japan’ to visit Toyota to see the difference between their operation and one that has been under continuous improvement for thirty years under the TPS. The following “seven wastes” identify resources which are commonly wasted. They were identified by Toyota’s Chief Engineer, Taiichi Ohno as part of the Toyota Production System:

There can be more forms of waste in addition to the seven. The 8 most common forms of waste can be remembered using the mnemonic “DOWNTIME” (Defective Production, Overproduction, Waiting, Non-used Employee Talent (the 8th form), Transportation, Inventory, Motion and Excessive (Over) Processing)

wastes clasification

Transportation

muda transportation

Each time a product is moved it stands the risk of being damaged, lost, delayed, etc. as well as being a cost for no added value. Transportation does not make any transformation to the product that the consumer is willing to pay for.

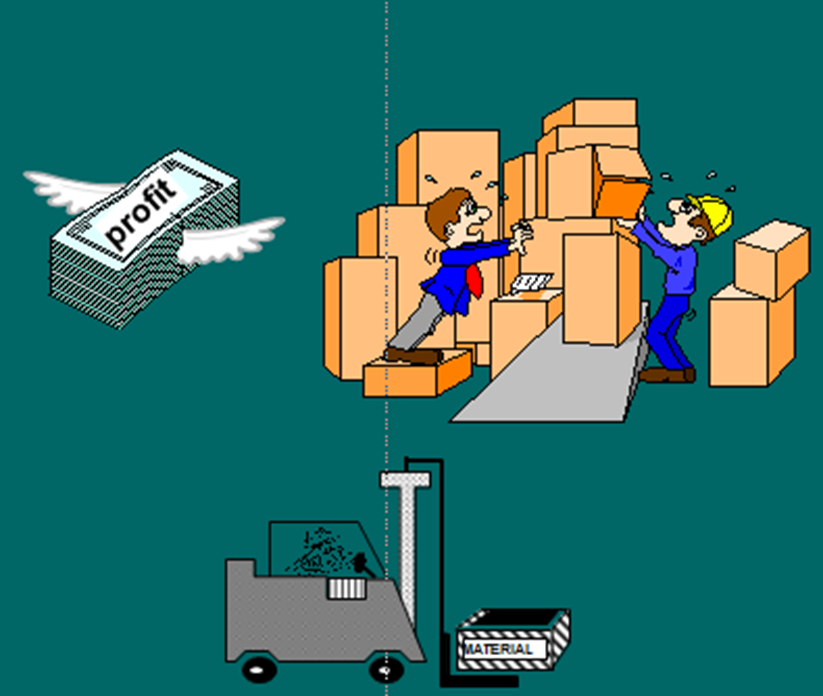

Inventory

muda inventory

Inventory, be it in the form of raw materials, work-in-progress (WIP), or finished goods, represents a capital outlay that has not yet produced an income either by the producer or for the consumer. Any of these three items not being actively processed to add value is waste.

Motion

muda motion

In contrast to transportation, which refers to damage to products and transaction costs associated with moving them, motion refers to the damage that the production process inflicts on the entity that creates the product, either over time (wear and tear for equipment and repetitive strain injuries for workers) or during discrete events (accidents that damage equipment and/or injure workers).

Waiting

muda waiting

Whenever goods are not in transport or being processed, they are waiting. In traditional processes, a large part of an individual product’s life is spent waiting to be worked on.

Over-processing

muda over processing

Over-processing occurs any time more work is done on a piece than is required by the customer. This also includes using components that are more precise, complex, higher quality or expensive than absolutely required.

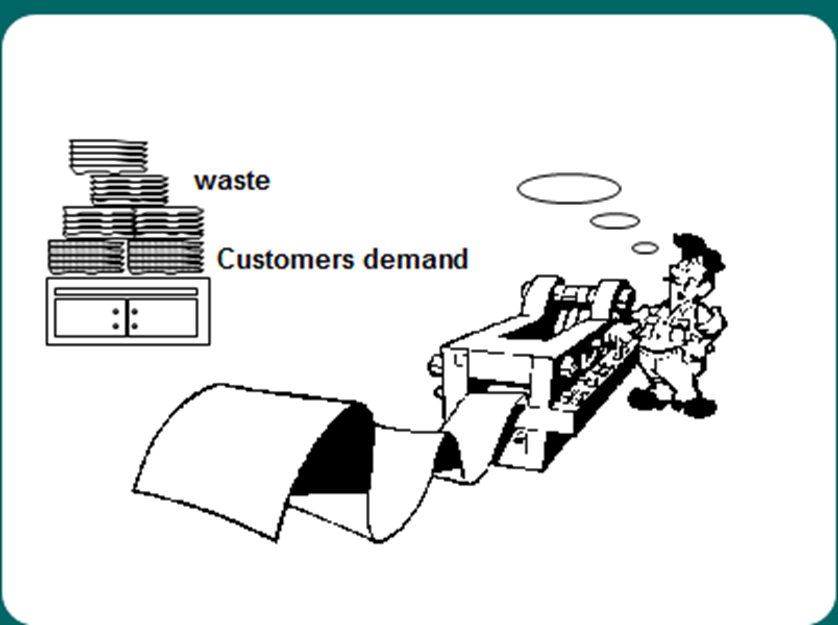

Over-production

muda over production

Overproduction occurs when more product is produced than is required at that time by your customers. One common practice that leads to this muda is the production of large batches, as often consumer needs change over the long times large batches require. Overproduction is considered the worst muda because it hides and/or generates all the others. Overproduction leads to excess inventory, which then requires the expenditure of resources on storage space and preservation, activities that do not benefit the customer.

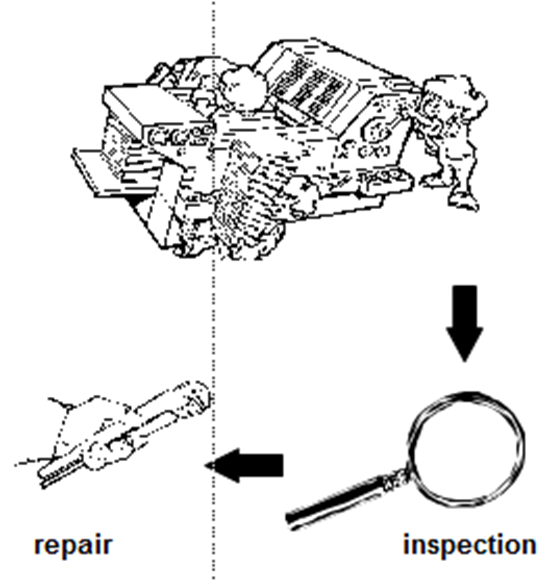

Defects

muda defects

Whenever defects occur, extra costs are incurred reworking the part, rescheduling production, etc. This results in labor costs, more time in the “Work-in-progress”. Defects in practice can sometimes double the cost of one single product. This should not be passed on to the consumer and should be taken as a loss.